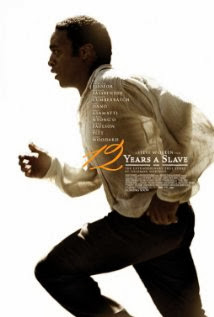

12 Years a Slave and Truth: Beyond Convention

The first time I met with my physical therapist, he told me that, in the future, I would have to weigh my pain against each situation. Knowing I had three children, he asked me if the pain of childbirth was worth it and then told me I would have to look at each situation and decide if the pain or discomfort was worth it. Last week, I made that decision three times. I decided to: walk, slowly, with my children as they trick-or-treated, accompany them to our parish All Saints Day party, and drive to watch 12 Years A Slave in a cinema. Yes, they were all worth the discomfort, which is significantly less than that which I was experiencing a few weeks ago, thanks be to God.

In this post, I wanted to write about the films of 12 Years a Slave director, Steve McQueen. I wanted to write about that film, in particular, in detail. I have pages of notes and lots of thoughts bouncing around in my head, but I can't approach that film--that story--in that manner, at least not right now. I don't want to spoil the story with details of the plot, so this post speaks to the beauty and genius of the work as part of the canon of Steve McQueen films. I cannot recommend this film highly enough. Every adult and mature teenager needs to see 12 Years a Slave.

Part of my longing for this story to be told on film is that I am from the Deep South, the Delta, to be specific. The only thing that generated more discussion amongst my classmates than "being saved" during revival season was the issue of slavery after a movie set in the antebellum south aired on television. I'm old enough that when a program like the mini series, North and South, based on the John Jakes novel, aired on ABC, everyone watched it as it aired and talked about it the next day. I remember a classmate walking up and down the aisles of desks before class began, asking each student, "Are you a Rebel or a Yankee?" That was 1985. At that time, the high school in our town still elected a white Homecoming Queen and a black Homecoming Queen. The school dances, including Homecoming and Prom, were "black" dances and the white parents of the Junior class helped the members of the all-white Junior Club hold whites-only dances off campus. At the Homecoming football game, black and white young ladies sat as part of the Homecoming court, attired in beautiful wool suits, hats, and leather gloves while black and white football players worked together to score points on the field. Later that evening, they parted ways, with the black students going to the dance on campus and the white students heading to a location off-campus.

Race and the history of the south was always present, either on the surface, or at a constant bubble below. How could it not be? Slavery is a fact of history. It was part of international trade and a foundation of our nation's economy before the Civil War. It should be a large part of schools' history curriculums (standards, objectives, textbooks). It has to be a part of our national debate because we haven't really faced it as a nation. Our national sins don't fit in with the image we have of ourselves as a nation. How can we learn from mistakes and improve if we don't examine our past? How can we grow closer to the ideals of our nation?

When I was in fifth grade, I visited a plantation home as part of a school field trip. The house was gorgeous with its sweeping, column-lined verandas and elegantly decorated rooms. At one point, we were shown a cut-away section of an interior wall. It was a bit disappointing and shocking to see how ugly the inside of the wall was. Lumpy, hand-made bricks, rough hewn timbers, and Spanish moss insulation formed the wall. Years later in tenth grade, I visited the LSU Rural Life Museum on another field trip. I recommend this as the first stop for anyone who wants to tour Plantation Country in the south. The museum is a living history site which shows how everyone other than the owners of the plantations would have lived. You can tour slave cabins, later sharecropper cabins, and other structures of the past for a better view of life in the past. As I stood in the cramped slave cabins and listened to the tour guide detail the daily life of slaves, my mind went back to the cross-section of wall I saw years before. Beneath the genteel beauty of a southern plantation home, there is a hidden, ugly truth which must be revealed to understand the structure of the whole. Steve Mc Queen's third film exposes part of that ugly truth for our modern eyes.

12 Years a Slave is a movie that forces viewers to confront some of the realities of slavery. Like McQueen's other major films, Hunger and Shame, it is stark, realistic, unflinching and haunting. I am not the same as I was when I sat down to watch the film last Saturday. My friend Megan and I saw it in an upscale shopping center that was created to look like a town square. We sat in the theatre until the last credit rolled, as a way of paying respect to every person involved in such a masterpiece. We walked out in silence, but had to make our way through posh shoppers, in that fake mock-up town square, to find a place to eat since we both had barely eaten all day. "This is just so wrong. It's just all so surreal after what we've just watched," Megan said as I noticed a Ferrari parked in front of me. After we sat down in the restaurant, we tried to process some of what we had just seen. Here's a bit of what we discussed and what has been going through my mind.

The memoir, Twelve Years a Slave is the true account of Soloman Northup who was a free black man living in Sarasota, New York when he was kidnapped and sold into slavery. He spent twelve years working on cotton and sugar plantations in the south. I think about that title and its meaning based on your point of view. For Soloman, he missed twelve whole years suffering, apart from his family. But what of twelve years in the life span of those born into the cruelty of slavery? It is a remarkable book about an extraordinary man. It should be a standard text in every high school in the United States and beyond. It is special in that we have the perspective of a man who was free and then found himself a part of that "peculiar institution." As readers, and viewers, we can identify a bit more with his story because of that element. I was also struck by the detail of the book, especially those pertaining to the work of Soloman as a slave and the daily life on the plantations. Most impressive and most lasting for me, though, was the soul and character of Soloman Northup. I've written before about my favorite fictional character, Jane Eyre, and her strength of character, but Soloman Northup is the real-life, true-story embodiment of all that made the fictional Jane so great. I was so moved by the lack of bitterness in his memoir. He made no excuses for sins of others, nor he did not justify actions or the institution of slavery, but he considered each person in his circumstances, including himself. Role model does not adequately describe what Mr. Northup should be for us all, especially our children.

There were a few changes and additions to the original story, but 12 Years strives for historical accuracy. The Oscar nominations should be many for this film and I hope costume and set designers are given a nod for this work. The locations used were real plantations, complete with the ghosts of the past. Mc Queen and his crew filmed in August and September. In south Louisiana. That's real sweat in the film, people. Many of the cast are from Great Britain and the heat and humidity of the filming location was a real assault. Actors have spoken to the authenticity it gave to the experience of portraying slavery and life at the time. The plantations which were used are not the most grand homes, such as Nottoway or Rosedown. They are still grand homes, but more realistic as being closer to what the majority of "big houses" would have looked like on plantations. The actual Epps home is still available for viewing. It is more humble than the home portrayed in the movie, as it was located further from the rich soil and crop yields of the Mississippi River, but I think viewers needed something like the location chosen to relate to their idea of a plantation. The chosen location is a good balance. The clothing is remarkable. You can actually see the texture of the fabrics, including those worn by the plantation families. These are not the grand silks, exaggerated hoop skirts and finery of films like Gone With the Wind. We get a more realistic view of how people of the time dressed and lived.

McQueen came to film-making as a visual artist. He did short films before making his first major motion picture, Hunger. The film blew me away and I can still get lost in thoughts about it. I had never seen anything quite like it. It was an introduction to McQueen as an artist and I can see his same fingerprints on 12 Years A Slave. When McQueen was asked why he made Hunger, he tells the story of filming, as an official war artist, in Iraq. When he returned, he wanted to see what "we" as British citizens, as a country had done closer to home. I was drained, but in some sort of satisfying way, as the film stayed with me and I continued to think upon it. After that experience, I began to search for every article and video interview with McQueen I could find. I had to hear more from the mind who made the film. I was not disappointed in those interviews. There was total complementarity between the man in the interviews and the maker of the film.

Hunger is the story of Bobby Sands, who led the 1981 Irish Republican Maze Prison hunger strike. The hunger strike was not only controversial because it was part of The Troubles of Northern Ireland, but also because of the moral debate as to whether or not Sands, a Roman Catholic, was committing suicide through his hunger strike. Before the strike begins, Sands calls in a priest. The scene portraying the dialogue between these two men is one of the greatest scenes in film. The writing is flawless, as is the acting, but it also showcases McQueen's use of a still camera shot. The camera does not move for about eighteen minutes. No close-ups on either actor. I watched McQueen say in an interview that he filmed it that way because that was natural and that when he listens to a real life conversation between two people, he's not constantly jerking his head back-and-forth to look at each of them. Not only is it natural, but it has the effect of holding your eye. You cannot look away.

The same long shots can be seen in 12 Years. The camera does not permit you to look away from the savagery of rape or whippings. The camera stays still during dialogues, also. You are a witness to the exchanges between characters. McQueen has stated that he doesn't want to insult his audience or their intelligence. He lets you experience the story and he leaves you to think it out. There is always a sparse musical score in his films. Every scene, even the most dramatic, does not need musical accompaniment to stir the audience. I remember being stunned by another long scene in Hunger, where a janitor is seen cleaning a prison hallway for what seems five minutes. That's it, but on film, within that particular film, it is purposeful and powerful. In 12 Years, freed from constant music, your senses are opened to the humanity of the characters, the silence and the natural sounds of their surroundings. The landscape of Louisiana is left on its own to throb and pulse with the heat, the humidity, the hum of cicadas and crickets. The land becomes, as it must in any story set in the deep south, another character in the film, affecting all the other characters. McQueen is not encumbered by the conventions of filmmaking and we are the benefactors.

Another trademark of Steve McQueen is his clarity of purpose when making a film. He doesn't have an agenda. When you finish watching Hunger, you really aren't sure with whose side his sympathies lie. In this interview, he describes his goal in making Hunger, which he considered more a reflection than a film:

With 12 Years, McQueen said he wanted to make a movie about slavery because there hadn't really been one before and because he wanted to be able to see slavery. He wanted to portray slavery so he could see it, to better understand it. He also said there was only one way to tell Soloman Northup's story: truthfully. And the truth is not always pretty. So, in 12 Years, we see slaves stripped nude, examined and judged as livestock, for purchase. As harsh and startling as that is, though, as tough as it is to watch beatings and hangings, probably the most horrific part of those scenes is that everyone in the scene, with the exception of Soloman as an outsider, and a few other characters, is carrying on as if it is all normal. Because, at the time, it was the norm.

I've seen writers bandy about the term "raw" to describe things like blog posts that are truthful, revealing or honest, but this film, along with McQueen's others, is truly raw. Brutality, savagery, jealousy, and lust are all portrayed in their fullness. His intention is never sensationalism or controversy, but instead just his attempt to truthfully tell a story. His second film, Shame, garnered much press and a NC-17 rating for its limited release. It is the fictional, though based on research, story of Brandon, who is a sex addict. In the film, the addiction also includes pornography. From the outside, he seems to be a handsome, successful New Yorker, who is well-liked, respected, and attractive to women. Mc Queen takes viewers beyond the exterior, though, to see how Brandon's addiction controls every part of his day. He is unable to get through his time at work without viewing pornography on his computer or making multiple trips to the bathroom. He has no normal relationships and real intimacy in any form is unattainable. When his sister shows up unannounced, things fall apart further as Brandon no longer has privacy in his own apartment. As is the case with a sibling, he can't rely on a false front; Sissy knows too much about him. Viewers are given clues to a shared past trauma between the siblings and hints that something horrible was a part of their childhoods. At one point, Sissy tells Brandon, "We're not bad people. We just come from a bad place." Raw? This is raw, as Sissy's presence finally leads to downward spiral of total depravity that is akin to what we would expect from a bender for an alcoholic or drug addict, but in the form of sexual encounters that become more and more impersonal than those we already saw from Brandon, who is so crippled by his addiction that he can relate in no other way to others. McQueen, his co-writer, and the actors met with real recovering sex addicts. They wanted to tell their stories, in truth.

But in Hunger, Shame, and 12 Years a Slave, we don't just see the sins or virtues of lead characters. We see the acts of everyone. We see each character making decisions where he is at that point, in the world in which he lives. Brandon's addiction is apparent, but we also see the broken nature of his sister's and his boss's sexuality. They are both attractive and get through their days looking fine to others, but we see damage and an inability to deal with others in any normal way. They all act according to their needs, with no consideration of the other person. His boss picks up women at bars and then sits as his office desk the next morning, talking to his children and wife through a camera. Shame is a movie about sex addiction, but it is the film McQueen describes as political. When questioned about this at a TIFF (Toronto International Film Festival) press conference, he explained that pornography is an issue we must all address, including the state, because its availability, particularly to the young, is unprecedented. He talked of how it is impairing our young people in their ability to have relationships or healthy views of their fellow man. We have to face the truth of a situation, even the full extent of its ugliness, before we can deal with it.

When reporters at the 2013 TIFF press conference stated 12 Years a Slave was a film about race or slavery, McQueen corrected them. "It's a film about love," he said. We see Soloman, strong and true to himself as best he can as a slave, but we see his motivation to get back to his wife and children. He wants them to understand he was kidnapped; he did not abandon them. He just wants to be back in his own home, with his own children again. And, again, we have slavery framed within the big idea that McQueen always explores: What does it mean to be human? A home, a family, freedom, life, love: these are all the most basic things to which every human being has a right. McQueen wants to explore all that we are capable of, from the depths to the heights, as human beings, and how our decisions and actions affect our neighbor and the wider world.

I don't know McQueen's personal spiritual beliefs, but I do know that all three of his major films speak to me, as I am a Catholic. I embrace the cross of Christ. As theologians have explained, there is the vertical element of the cross--my relationship with God--and the horizontal element which is God's relationship to all of humanity along with my relationship to my fellow man, regardless of his race or creed. In order to exercise the horizontal, I must nurture the vertical and grow closer to God through prayer and reflection. McQueen's films Hunger and 12 Years a Slave show characters of faith trying to do just that. They are looking for that balance and they are considering God's will as guidance, not as justification. It is debated on-screen, before our eyes, in Sands' conversation with his priestly confessor in Hunger and in Patsy's plea to Soloman in 12 Years a Slave. Viewers are left to decide. This is true thought and debate, real and essential to the characters' lives.

Also, to my Catholic sensibilities, McQueen's work has something of the liturgical about it. As I have said above, every use of camera shots, face, music, silence has a purpose for the telling of the story, not just as a convention or experiment. It is as if the external devices of film-making are ordered to the truth he wishes to tell. There is a proper order where the cast, crew, director--people as a communal-- and props are in service to that goal. With his background as a visual artist, Mc Queen understands the power of sign and symbol. They drive his movies, not the narration or dialogue. His films are not word-driven. They leave room for the audience to become a participant as the film accurately portrays reality, not a dramatization of the real world.

All three of his major films portray the Culture of Death, as John Paul II described our current times, where much of our society lives as if human beings are simply physical bodies, without eternal souls. The Church defines death as that moment when the soul leaves the body, thus the term Culture of Death to describe a time which includes crimes and abuses against humans and their dignity. Slavery would never exist as an institution if we viewed every person as equal in dignity. The Troubles in Ireland could not have happened if both sides saw the humanity in their opponent. And the sexual abuse and brokenness of Shame are a result of human beings being considered only as a body to be used for self-hate or self-pleasure.

I have read some reviews which hail 12 Years a Slave as McQueen's masterpiece because it is the more polished and less "artsy" of his three films. Some reviewers consider it the most mainstream, although still maybe not completely accessible because of its graphic portrayal of slavery. Although the film stands alone as a masterpiece, I think its fullness cannot be fully appreciated unless it is viewed in the context of the McQueen film canon and in conjunction with a reading of the memoir upon which it is based.

In the 2013 TIFF press conference video above, the majority of the cast of 12 Years a Slave was present to discuss the film. One exchange between the amazing Alfrie Woodard and a reporter was especially powerful for me. Woodard cautions against generalizing the white characters in the film as evil and making judgments about her own character's choices. She says people often boast of what they would have done if they lived during that time, but we have to look at the people as a part of their time. She went further to say that she is now a woman living under a system of Capitalism. She can't change that, just as the characters in the film were living under an economic system which hinged on slavery. She said she has to wake up each day and make the best decisions she can in the circumstances in which she finds herself.

So, when I watch McQueen's film, I also think of myself and consider the decisions I make. Yes, I'd like to think I would have been an abolitionist in antebellum times, but what of my athletic shoes I wear today that were probably made in sweat shops? What of the chocolate and coffee in our pantry that was not all made according to fair-trade practices? The true success of 12 Years a Slave is the true success of all McQueen's films. It is what makes them marvels or art and which justifies the use of the word "genius" to describe the director. His work is art that stirs your mind, heart, and soul. As the final credits roll and the film ends, your own examination of conscience begins.

In this post, I wanted to write about the films of 12 Years a Slave director, Steve McQueen. I wanted to write about that film, in particular, in detail. I have pages of notes and lots of thoughts bouncing around in my head, but I can't approach that film--that story--in that manner, at least not right now. I don't want to spoil the story with details of the plot, so this post speaks to the beauty and genius of the work as part of the canon of Steve McQueen films. I cannot recommend this film highly enough. Every adult and mature teenager needs to see 12 Years a Slave.

Part of my longing for this story to be told on film is that I am from the Deep South, the Delta, to be specific. The only thing that generated more discussion amongst my classmates than "being saved" during revival season was the issue of slavery after a movie set in the antebellum south aired on television. I'm old enough that when a program like the mini series, North and South, based on the John Jakes novel, aired on ABC, everyone watched it as it aired and talked about it the next day. I remember a classmate walking up and down the aisles of desks before class began, asking each student, "Are you a Rebel or a Yankee?" That was 1985. At that time, the high school in our town still elected a white Homecoming Queen and a black Homecoming Queen. The school dances, including Homecoming and Prom, were "black" dances and the white parents of the Junior class helped the members of the all-white Junior Club hold whites-only dances off campus. At the Homecoming football game, black and white young ladies sat as part of the Homecoming court, attired in beautiful wool suits, hats, and leather gloves while black and white football players worked together to score points on the field. Later that evening, they parted ways, with the black students going to the dance on campus and the white students heading to a location off-campus.

Race and the history of the south was always present, either on the surface, or at a constant bubble below. How could it not be? Slavery is a fact of history. It was part of international trade and a foundation of our nation's economy before the Civil War. It should be a large part of schools' history curriculums (standards, objectives, textbooks). It has to be a part of our national debate because we haven't really faced it as a nation. Our national sins don't fit in with the image we have of ourselves as a nation. How can we learn from mistakes and improve if we don't examine our past? How can we grow closer to the ideals of our nation?

When I was in fifth grade, I visited a plantation home as part of a school field trip. The house was gorgeous with its sweeping, column-lined verandas and elegantly decorated rooms. At one point, we were shown a cut-away section of an interior wall. It was a bit disappointing and shocking to see how ugly the inside of the wall was. Lumpy, hand-made bricks, rough hewn timbers, and Spanish moss insulation formed the wall. Years later in tenth grade, I visited the LSU Rural Life Museum on another field trip. I recommend this as the first stop for anyone who wants to tour Plantation Country in the south. The museum is a living history site which shows how everyone other than the owners of the plantations would have lived. You can tour slave cabins, later sharecropper cabins, and other structures of the past for a better view of life in the past. As I stood in the cramped slave cabins and listened to the tour guide detail the daily life of slaves, my mind went back to the cross-section of wall I saw years before. Beneath the genteel beauty of a southern plantation home, there is a hidden, ugly truth which must be revealed to understand the structure of the whole. Steve Mc Queen's third film exposes part of that ugly truth for our modern eyes.

12 Years a Slave is a movie that forces viewers to confront some of the realities of slavery. Like McQueen's other major films, Hunger and Shame, it is stark, realistic, unflinching and haunting. I am not the same as I was when I sat down to watch the film last Saturday. My friend Megan and I saw it in an upscale shopping center that was created to look like a town square. We sat in the theatre until the last credit rolled, as a way of paying respect to every person involved in such a masterpiece. We walked out in silence, but had to make our way through posh shoppers, in that fake mock-up town square, to find a place to eat since we both had barely eaten all day. "This is just so wrong. It's just all so surreal after what we've just watched," Megan said as I noticed a Ferrari parked in front of me. After we sat down in the restaurant, we tried to process some of what we had just seen. Here's a bit of what we discussed and what has been going through my mind.

The memoir, Twelve Years a Slave is the true account of Soloman Northup who was a free black man living in Sarasota, New York when he was kidnapped and sold into slavery. He spent twelve years working on cotton and sugar plantations in the south. I think about that title and its meaning based on your point of view. For Soloman, he missed twelve whole years suffering, apart from his family. But what of twelve years in the life span of those born into the cruelty of slavery? It is a remarkable book about an extraordinary man. It should be a standard text in every high school in the United States and beyond. It is special in that we have the perspective of a man who was free and then found himself a part of that "peculiar institution." As readers, and viewers, we can identify a bit more with his story because of that element. I was also struck by the detail of the book, especially those pertaining to the work of Soloman as a slave and the daily life on the plantations. Most impressive and most lasting for me, though, was the soul and character of Soloman Northup. I've written before about my favorite fictional character, Jane Eyre, and her strength of character, but Soloman Northup is the real-life, true-story embodiment of all that made the fictional Jane so great. I was so moved by the lack of bitterness in his memoir. He made no excuses for sins of others, nor he did not justify actions or the institution of slavery, but he considered each person in his circumstances, including himself. Role model does not adequately describe what Mr. Northup should be for us all, especially our children.

There were a few changes and additions to the original story, but 12 Years strives for historical accuracy. The Oscar nominations should be many for this film and I hope costume and set designers are given a nod for this work. The locations used were real plantations, complete with the ghosts of the past. Mc Queen and his crew filmed in August and September. In south Louisiana. That's real sweat in the film, people. Many of the cast are from Great Britain and the heat and humidity of the filming location was a real assault. Actors have spoken to the authenticity it gave to the experience of portraying slavery and life at the time. The plantations which were used are not the most grand homes, such as Nottoway or Rosedown. They are still grand homes, but more realistic as being closer to what the majority of "big houses" would have looked like on plantations. The actual Epps home is still available for viewing. It is more humble than the home portrayed in the movie, as it was located further from the rich soil and crop yields of the Mississippi River, but I think viewers needed something like the location chosen to relate to their idea of a plantation. The chosen location is a good balance. The clothing is remarkable. You can actually see the texture of the fabrics, including those worn by the plantation families. These are not the grand silks, exaggerated hoop skirts and finery of films like Gone With the Wind. We get a more realistic view of how people of the time dressed and lived.

McQueen came to film-making as a visual artist. He did short films before making his first major motion picture, Hunger. The film blew me away and I can still get lost in thoughts about it. I had never seen anything quite like it. It was an introduction to McQueen as an artist and I can see his same fingerprints on 12 Years A Slave. When McQueen was asked why he made Hunger, he tells the story of filming, as an official war artist, in Iraq. When he returned, he wanted to see what "we" as British citizens, as a country had done closer to home. I was drained, but in some sort of satisfying way, as the film stayed with me and I continued to think upon it. After that experience, I began to search for every article and video interview with McQueen I could find. I had to hear more from the mind who made the film. I was not disappointed in those interviews. There was total complementarity between the man in the interviews and the maker of the film.

Hunger is the story of Bobby Sands, who led the 1981 Irish Republican Maze Prison hunger strike. The hunger strike was not only controversial because it was part of The Troubles of Northern Ireland, but also because of the moral debate as to whether or not Sands, a Roman Catholic, was committing suicide through his hunger strike. Before the strike begins, Sands calls in a priest. The scene portraying the dialogue between these two men is one of the greatest scenes in film. The writing is flawless, as is the acting, but it also showcases McQueen's use of a still camera shot. The camera does not move for about eighteen minutes. No close-ups on either actor. I watched McQueen say in an interview that he filmed it that way because that was natural and that when he listens to a real life conversation between two people, he's not constantly jerking his head back-and-forth to look at each of them. Not only is it natural, but it has the effect of holding your eye. You cannot look away.

The same long shots can be seen in 12 Years. The camera does not permit you to look away from the savagery of rape or whippings. The camera stays still during dialogues, also. You are a witness to the exchanges between characters. McQueen has stated that he doesn't want to insult his audience or their intelligence. He lets you experience the story and he leaves you to think it out. There is always a sparse musical score in his films. Every scene, even the most dramatic, does not need musical accompaniment to stir the audience. I remember being stunned by another long scene in Hunger, where a janitor is seen cleaning a prison hallway for what seems five minutes. That's it, but on film, within that particular film, it is purposeful and powerful. In 12 Years, freed from constant music, your senses are opened to the humanity of the characters, the silence and the natural sounds of their surroundings. The landscape of Louisiana is left on its own to throb and pulse with the heat, the humidity, the hum of cicadas and crickets. The land becomes, as it must in any story set in the deep south, another character in the film, affecting all the other characters. McQueen is not encumbered by the conventions of filmmaking and we are the benefactors.

Another trademark of Steve McQueen is his clarity of purpose when making a film. He doesn't have an agenda. When you finish watching Hunger, you really aren't sure with whose side his sympathies lie. In this interview, he describes his goal in making Hunger, which he considered more a reflection than a film:

I wanted to look at the Left and the Right of it all and have Left and Right in one room having that kind of dialogue. It's almost two stones and what do you want them to do in that situation? Make fire, with that film, obviously, within that sort-of contained situation, in that room, and to hold it for a moment, and hope it was bright for a moment in order to contemplate, think and reflect.

With 12 Years, McQueen said he wanted to make a movie about slavery because there hadn't really been one before and because he wanted to be able to see slavery. He wanted to portray slavery so he could see it, to better understand it. He also said there was only one way to tell Soloman Northup's story: truthfully. And the truth is not always pretty. So, in 12 Years, we see slaves stripped nude, examined and judged as livestock, for purchase. As harsh and startling as that is, though, as tough as it is to watch beatings and hangings, probably the most horrific part of those scenes is that everyone in the scene, with the exception of Soloman as an outsider, and a few other characters, is carrying on as if it is all normal. Because, at the time, it was the norm.

I've seen writers bandy about the term "raw" to describe things like blog posts that are truthful, revealing or honest, but this film, along with McQueen's others, is truly raw. Brutality, savagery, jealousy, and lust are all portrayed in their fullness. His intention is never sensationalism or controversy, but instead just his attempt to truthfully tell a story. His second film, Shame, garnered much press and a NC-17 rating for its limited release. It is the fictional, though based on research, story of Brandon, who is a sex addict. In the film, the addiction also includes pornography. From the outside, he seems to be a handsome, successful New Yorker, who is well-liked, respected, and attractive to women. Mc Queen takes viewers beyond the exterior, though, to see how Brandon's addiction controls every part of his day. He is unable to get through his time at work without viewing pornography on his computer or making multiple trips to the bathroom. He has no normal relationships and real intimacy in any form is unattainable. When his sister shows up unannounced, things fall apart further as Brandon no longer has privacy in his own apartment. As is the case with a sibling, he can't rely on a false front; Sissy knows too much about him. Viewers are given clues to a shared past trauma between the siblings and hints that something horrible was a part of their childhoods. At one point, Sissy tells Brandon, "We're not bad people. We just come from a bad place." Raw? This is raw, as Sissy's presence finally leads to downward spiral of total depravity that is akin to what we would expect from a bender for an alcoholic or drug addict, but in the form of sexual encounters that become more and more impersonal than those we already saw from Brandon, who is so crippled by his addiction that he can relate in no other way to others. McQueen, his co-writer, and the actors met with real recovering sex addicts. They wanted to tell their stories, in truth.

But in Hunger, Shame, and 12 Years a Slave, we don't just see the sins or virtues of lead characters. We see the acts of everyone. We see each character making decisions where he is at that point, in the world in which he lives. Brandon's addiction is apparent, but we also see the broken nature of his sister's and his boss's sexuality. They are both attractive and get through their days looking fine to others, but we see damage and an inability to deal with others in any normal way. They all act according to their needs, with no consideration of the other person. His boss picks up women at bars and then sits as his office desk the next morning, talking to his children and wife through a camera. Shame is a movie about sex addiction, but it is the film McQueen describes as political. When questioned about this at a TIFF (Toronto International Film Festival) press conference, he explained that pornography is an issue we must all address, including the state, because its availability, particularly to the young, is unprecedented. He talked of how it is impairing our young people in their ability to have relationships or healthy views of their fellow man. We have to face the truth of a situation, even the full extent of its ugliness, before we can deal with it.

When reporters at the 2013 TIFF press conference stated 12 Years a Slave was a film about race or slavery, McQueen corrected them. "It's a film about love," he said. We see Soloman, strong and true to himself as best he can as a slave, but we see his motivation to get back to his wife and children. He wants them to understand he was kidnapped; he did not abandon them. He just wants to be back in his own home, with his own children again. And, again, we have slavery framed within the big idea that McQueen always explores: What does it mean to be human? A home, a family, freedom, life, love: these are all the most basic things to which every human being has a right. McQueen wants to explore all that we are capable of, from the depths to the heights, as human beings, and how our decisions and actions affect our neighbor and the wider world.

This press conference begins with the trailer for 12 Years a Slave.

I don't know McQueen's personal spiritual beliefs, but I do know that all three of his major films speak to me, as I am a Catholic. I embrace the cross of Christ. As theologians have explained, there is the vertical element of the cross--my relationship with God--and the horizontal element which is God's relationship to all of humanity along with my relationship to my fellow man, regardless of his race or creed. In order to exercise the horizontal, I must nurture the vertical and grow closer to God through prayer and reflection. McQueen's films Hunger and 12 Years a Slave show characters of faith trying to do just that. They are looking for that balance and they are considering God's will as guidance, not as justification. It is debated on-screen, before our eyes, in Sands' conversation with his priestly confessor in Hunger and in Patsy's plea to Soloman in 12 Years a Slave. Viewers are left to decide. This is true thought and debate, real and essential to the characters' lives.

Also, to my Catholic sensibilities, McQueen's work has something of the liturgical about it. As I have said above, every use of camera shots, face, music, silence has a purpose for the telling of the story, not just as a convention or experiment. It is as if the external devices of film-making are ordered to the truth he wishes to tell. There is a proper order where the cast, crew, director--people as a communal-- and props are in service to that goal. With his background as a visual artist, Mc Queen understands the power of sign and symbol. They drive his movies, not the narration or dialogue. His films are not word-driven. They leave room for the audience to become a participant as the film accurately portrays reality, not a dramatization of the real world.

All three of his major films portray the Culture of Death, as John Paul II described our current times, where much of our society lives as if human beings are simply physical bodies, without eternal souls. The Church defines death as that moment when the soul leaves the body, thus the term Culture of Death to describe a time which includes crimes and abuses against humans and their dignity. Slavery would never exist as an institution if we viewed every person as equal in dignity. The Troubles in Ireland could not have happened if both sides saw the humanity in their opponent. And the sexual abuse and brokenness of Shame are a result of human beings being considered only as a body to be used for self-hate or self-pleasure.

I have read some reviews which hail 12 Years a Slave as McQueen's masterpiece because it is the more polished and less "artsy" of his three films. Some reviewers consider it the most mainstream, although still maybe not completely accessible because of its graphic portrayal of slavery. Although the film stands alone as a masterpiece, I think its fullness cannot be fully appreciated unless it is viewed in the context of the McQueen film canon and in conjunction with a reading of the memoir upon which it is based.

In the 2013 TIFF press conference video above, the majority of the cast of 12 Years a Slave was present to discuss the film. One exchange between the amazing Alfrie Woodard and a reporter was especially powerful for me. Woodard cautions against generalizing the white characters in the film as evil and making judgments about her own character's choices. She says people often boast of what they would have done if they lived during that time, but we have to look at the people as a part of their time. She went further to say that she is now a woman living under a system of Capitalism. She can't change that, just as the characters in the film were living under an economic system which hinged on slavery. She said she has to wake up each day and make the best decisions she can in the circumstances in which she finds herself.

So, when I watch McQueen's film, I also think of myself and consider the decisions I make. Yes, I'd like to think I would have been an abolitionist in antebellum times, but what of my athletic shoes I wear today that were probably made in sweat shops? What of the chocolate and coffee in our pantry that was not all made according to fair-trade practices? The true success of 12 Years a Slave is the true success of all McQueen's films. It is what makes them marvels or art and which justifies the use of the word "genius" to describe the director. His work is art that stirs your mind, heart, and soul. As the final credits roll and the film ends, your own examination of conscience begins.

Part 2 of 2 posts about searches for truth in the world of film and television.

Comments

Post a Comment

Your comments are welcome!